1st round 2023 to 2024 Community in Coexistence: Nan Fung education team members' sharing

Human (students) : Nature

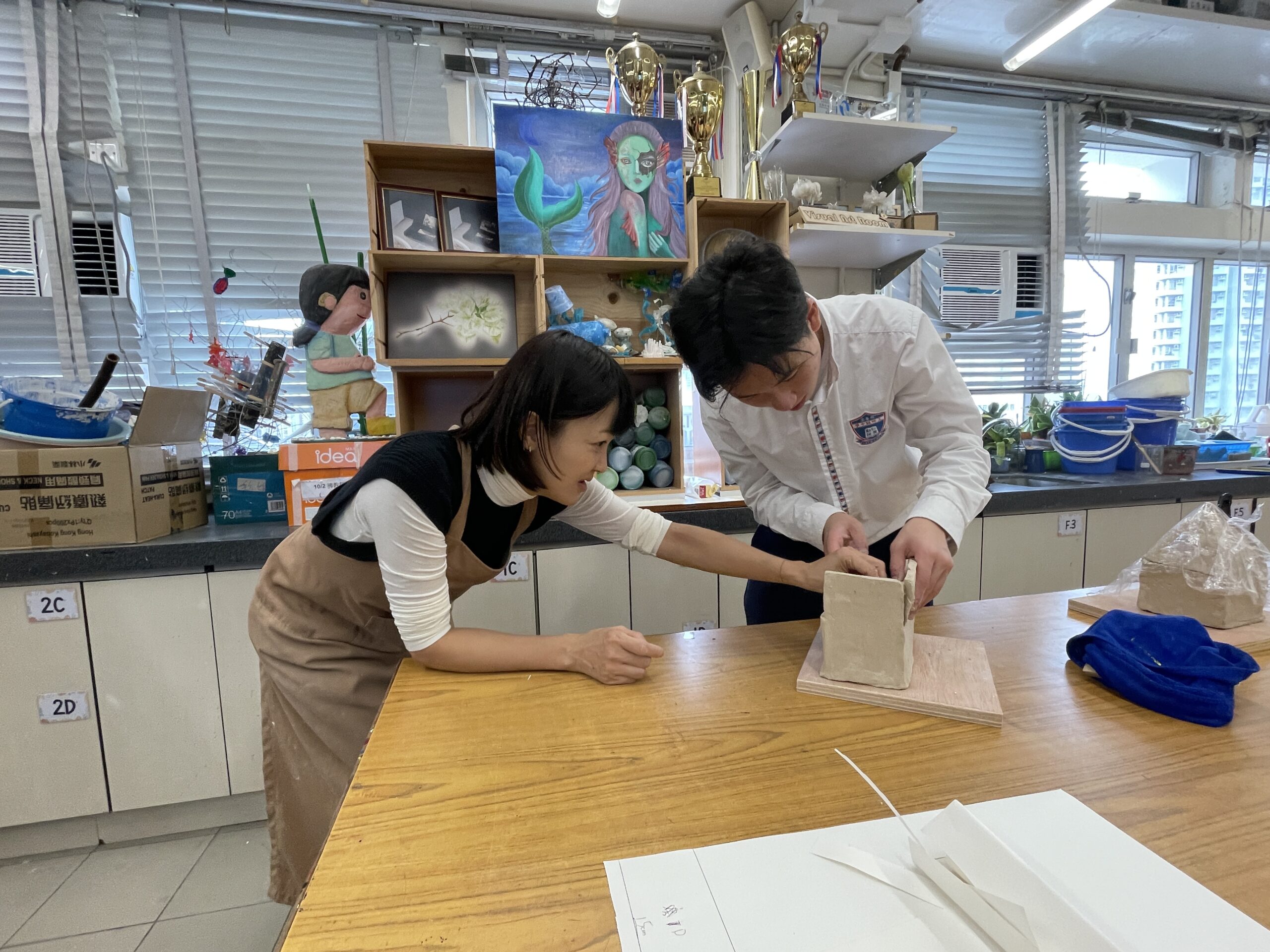

Rebeka Tam, Arts Educator on Ceramics at Lok Sin Tong Wong Chung Ming Secondary School

In recent years, I’ve been more focused on my own creative work and teaching, and I thought I probably wouldn’t have the chance to teach in secondary schools or take part in this kind of collaborative arts education program again. When I heard that Sandy, a longtime collaborator, had a new initiative, I agreed right away.

Looking back on the arts education projects I’ve taken part in, I find myself wondering: as an artist participant, what would count as having participated in a “good” project?

First, there must be a trustworthy leader and a team willing to assist. Arts education emphasizes students’ own experiences and understanding. I remember that at the first meeting where we discussed the workshop design, Sandy asked us the art instructors: How do we define “Coexistence”? Try to explain it in a single word. The fact that Sandy asked this indicates that “Coexistence” is the very spirit of the workshop. Although Sandy and I have collaborated on several art projects related to “Coexistence”, when asked again at different times and in different contexts, my perspective is always slightly different.

I remember the word “emergence” surfacing in my mind at the time. When applied to education, “coexistence” is a process of mutual influence and interactive co-formation. So before the project began, we only had the broad structural outline of the course; the content wasn’t fixed rigidly. What followed depended on post-class reflections each time and on shaping subsequent content according to students’ abilities and interests. In the end, how the students’ art works evolved was determined by the interactions that occurred throughout the process. This is probably what makes arts education so engaging.

Students had to jump from regular classes into an art-creation mode, which was a challenge for those who weren’t particularly interested in art. Because we hoped they would step outside the classroom and explore the themes of waterways and the community from different perspectives, they had to go out for fieldwork in the hills, interview strangers, think creatively, give oral presentations, knead clay, and make crafts… It posed considerable challenges across physical stamina, mental effort, and manual skills.

We often talk about the “process”. What, in fact, does the process of arts education encompass? “Coexistence” entails mutual respect, and in designing the curriculum I hope to include both group and individual creative components, so that while students try to express their ideas, they also learn the importance of listening to and respecting different perspectives. As an art instructor, the happiest moments are when I see students get the chance to immerse themselves in their own creations; for today’s busy new generation of students, having time to focus on completing a single task is such a luxury.

Ceramics is a highly tactile form of creation, and clay has a physical character on its own. In the creative process, close attention is paid to the technical details of shaping and construction, to moisture management, and one must also learn to face the possibility of failure after firing. For me, these material characteristics are also where the magic of ceramics education lies.

The value of arts education lies in respecting different ideas; ideas are neither great nor minor, right nor wrong—this is only a starting point. Even the smallest idea has the chance to evolve into a great idea. We also hope, through art, to make students’ diverse abilities visible; even those who are not usually adept at verbal expression have the opportunity to express unique ideas and craftsmanship through their creations. All of the above are what I have always regarded as the values of art education; emphasizing the value of pluralistic diversity —”coexistence”—is especially important today.

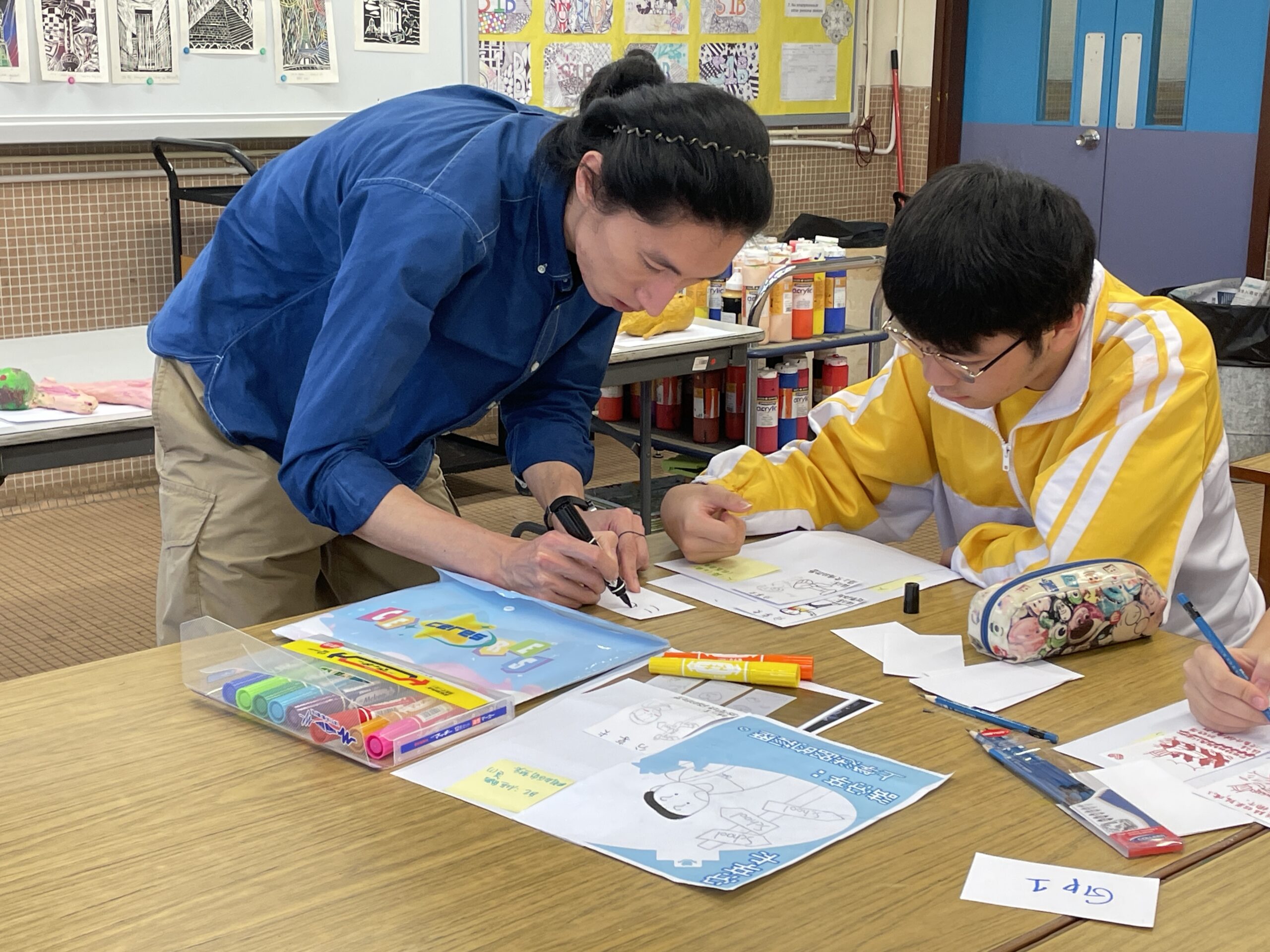

Sunny Wong, Arts Educator on mixed media at Christian Alliance Cheng Wing Gee College and Lok Sin Tong Wong Chung Ming Secondary School

Even if you see the cashier at the convenience store every day, I suppose few people would describe that as a particularly close relationship.

The same situation shows up in the two schools where I lead the workshops. Students from different classes come together for the workshop; there are classmates you often pass on campus but may never have exchanged a word with, and in front stand a few unfamiliar faces from outside. At the beginning, it’s only natural that everyone seems a bit shy. Fortunately, “relationships” aren’t set in stone.

In the subsequent classes, we built rapport with one another while exploring the coexistence among different things in life. At first, I also felt that “coexistence” sounded very academic and abstract. But as we shared and learned together in the workshop, it kind of clicked all of a sudden one day : hey—isn’t this basically what we often say, “try to look at things more from other people’s perspective”?

This “other people” can be broad or narrow. On a small scale, when two people approach each other on the street, each adjusts their path slightly at the right moment to avoid bumping into each other. On a large scale, it’s about the development of civilization—how to think about urban design from the standpoint of nature and ecological balance.

Some students have devised new streetlight designs in hopes of providing birds with more places to rest; others have launched an observation project to understand the daily routine of the security guard downstairs at their building; and some others have used game cards to prompt everyone to think about when a familiar place can suddenly become unfamiliar. Focusing on people, nature, and space, these creations present us with a variety of entry points for thinking about coexistence.

Of course a brief workshop are only a beginning. Recently, I also learned that upon shopping, I can show the product’s barcode toward the cashier ahead to make it easier for them to scan. For one thing, it makes their day a bit easier (and if everyone did this, it might be more than just a bit); for another, if I’m in a hurry too, it’s a win-win.

Let’s keep learning how to build a good relationship with this world.

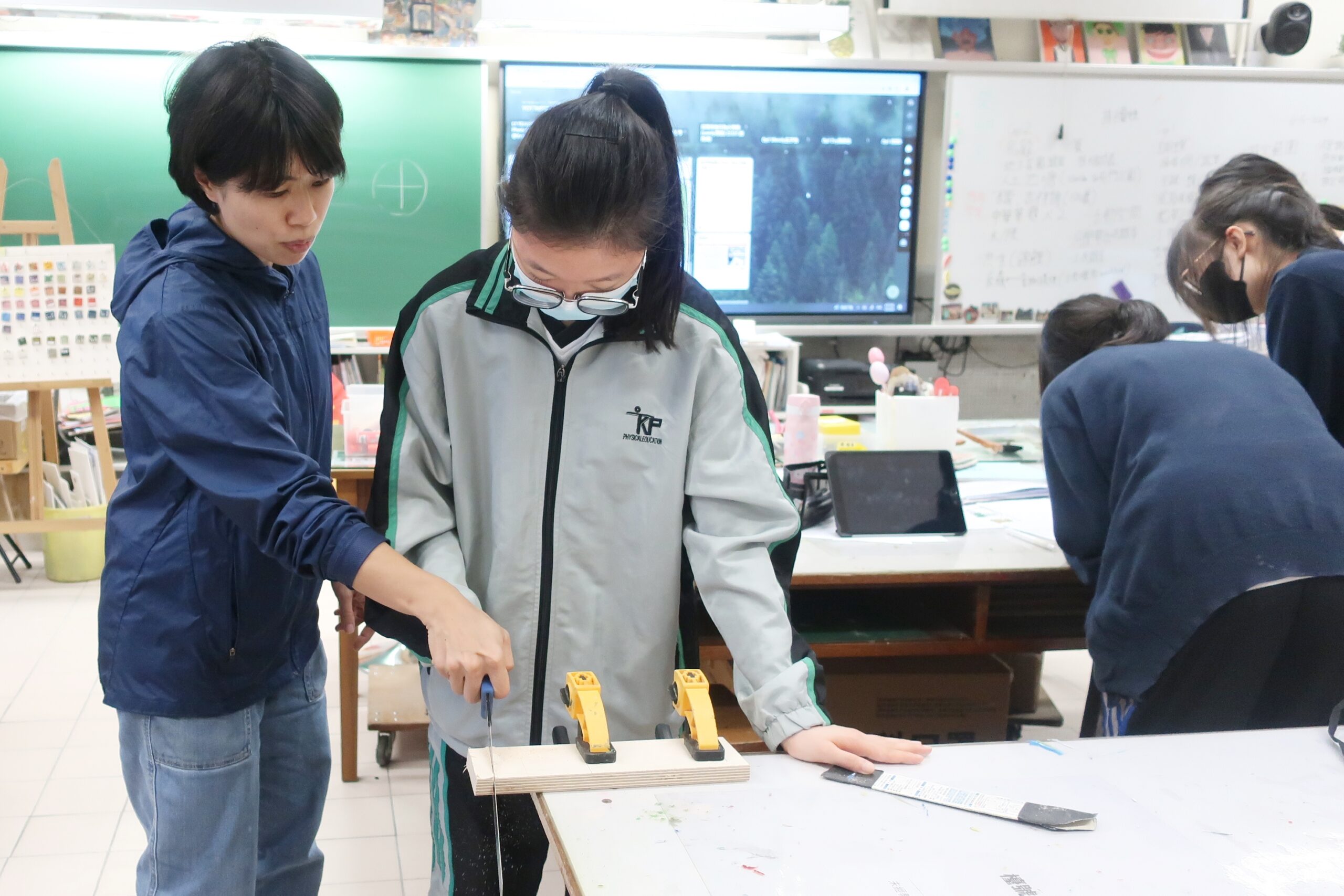

Chung Wai Ian, Arts Educator on Woodwork at Yan Oi Tong Tin Ka Ping Secondary School

Create a “home for turtles”, with the hope that the baby turtle will be jointly cared for by various generations of students at the school and grow up together with them, becoming a link that connects graduates across different cohorts. Create a “home for butterflies” for schoolmates who dislike butterflies, hoping to create coexistent living spaces on campus for those students who fear insects and the fragile little living creatures. These are two “animal homes” created by six Visual Arts students at Yan Oi Tong Tin Ka Ping Secondary School. With consideration on the animals’ needs and, within a man-made environment, students designed prototype works that also incorporated nature-inspired elements and aligned with the animals’ habitat characteristics, enabling animals and people to coexist in harmony on campus.

At the early stage of the “In Time Of – Co-Learning Squad” project, under the guidance of ecological educator Louis Fung, the students from Tin Ka Ping Secondary School and myself explored Tuen Mun Park—a public space where the artificial and the natural intermingle—to reflect on the reciprocal relationship between humans and nature, while also discovering various animal survival habits. We found that the park has stands of banyan trees; the figs on these trees are food for birds, and tree hollows or the crisscrossing gaps among branches provide them with spaces for nesting and breeding. But when we looked closely at the nests in the trees, we found plastic bags interwoven among the fine twigs.

During the field study, we invited students to collect fallen leaves, dead branches, and stones in the park, learning to incorporate reclaimed local natural materials into site-specific small creative exercises. They created temporary “animal homes” in response to their observations and experiences during the fieldwork. For example, a “turtle home” was made by seemingly casually using an acacia wood block shaped like a small slope—an idea drawn from the visual memory, during our visit to the artificial lake, of noticing turtles basking on the sloped lakeside.

Although this “In Time Of – Co-Learning Squad” project was organized in collaboration with only Visual Arts subject, we believe students gained profound and interesting learning related to Geography and the ecological environment. One student shared that she wrote an essay in her Chinese class about her observations and feelings from the field study at Tuen Mun Park. Her self-initiated, integrative writing enabled the activity to achieve its goal of interdisciplinary, self-directed learning.

Louis Fung, Ecology Educator at all the three participating schools

Article Title : Discoveries from the guided study tour

Lok Sin Tong Wong Chung Ming Secondary School – Tan Shan River, Fanling North X Kai Tak River

On the morning of the field study, a heavy downpour made the mountain trail slippery, greatly increasing the difficulty of the hike. Yet not a single student giving up—truly worthy of praise.

Along the way, some students noticed a large number of ants scurrying chaotically on a retaining wall. Affected by flooding, the ants were hurriedly fleeing their nest. The students felt that in today’s era of increasingly frequent extreme weather, ants are affected just as we are.

Another field site was the Kai Tak River beside the school. The weather that day was fine and sunny, the students worked hard to complete a questionnaire survey of neighbourhood residents. Afterwards, they showed great seriousness and diligence during the learning process about the egrets in the river and the fish they prey on, as well as their coexistence relationships with the residents.

Christian Alliance Cheng Wing Gee College — Tai Po River

After assembling at the train station, the students were invited to touch man-made structures to feel their temperature and texture. When we walked to the park next to the station, they were then invited to touch the large trees to compare environmental factors and share their impressions; everyone did so without hesitation. Upon arriving at the egret resting neighbourhood, we saw many egrets on their nests, with quite a few chicks foraging. The students were very excited, yet they knew how to respect the birds—only watching or asking questions in soft voices—achieving peaceful coexistence. The route for this field study was not short, but the students moved quickly. After reaching the rocky shore, they eagerly helped look for crabs and learn about their habitats, which made the field trip complete.

Yan Oi Tong Tin Ka Ping Secondary School — Tuen Mun River

Most of the field trip took place in Tuen Mun Park, where the students were clearly focused on understanding what an “animal’s home” is. Not long after we started, we found a black-collared starling’s nest in a tree—the nesting materials even included plastic tape! The students were surprised; it’s clearly unnatural for birds to use such a long-lasting harmful material. We then discovered a sparrow’s nest, an Asian koel up to no good, and flocks of birds joining forces to drive the koel away, as well as red-eared sliders courting and basking in the sunlight, night herons lying in ambush, and fish in the Tuen Mun River. The students were full of curiosity and interest, listened attentively and asked timely questions, lastly they realized that this place, the park is their home.

Share